Treaty to Protect Ocean Biodiversity Ratified

High Seas Treaty Will Enter Force in January 2026

The biodiversity-focused United Nations High Seas Treaty (HST)1 has now been ratified by 60 countries, triggering its entry into force in January 2026.

The HST represents a major milestone in marine conservation, as it seeks for the first time to protect biodiversity in international waters. It has been signed by 145 nations, including most of the world’s maritime powers (with the notable exceptions of Russia and Japan).

It required ratification by sixty of these nations before coming into effect. Morocco became the 60th country to ratify on September 19th.2 It has since been joined by 15 additional ratifiers, the latest being Palestine on October 1st.3

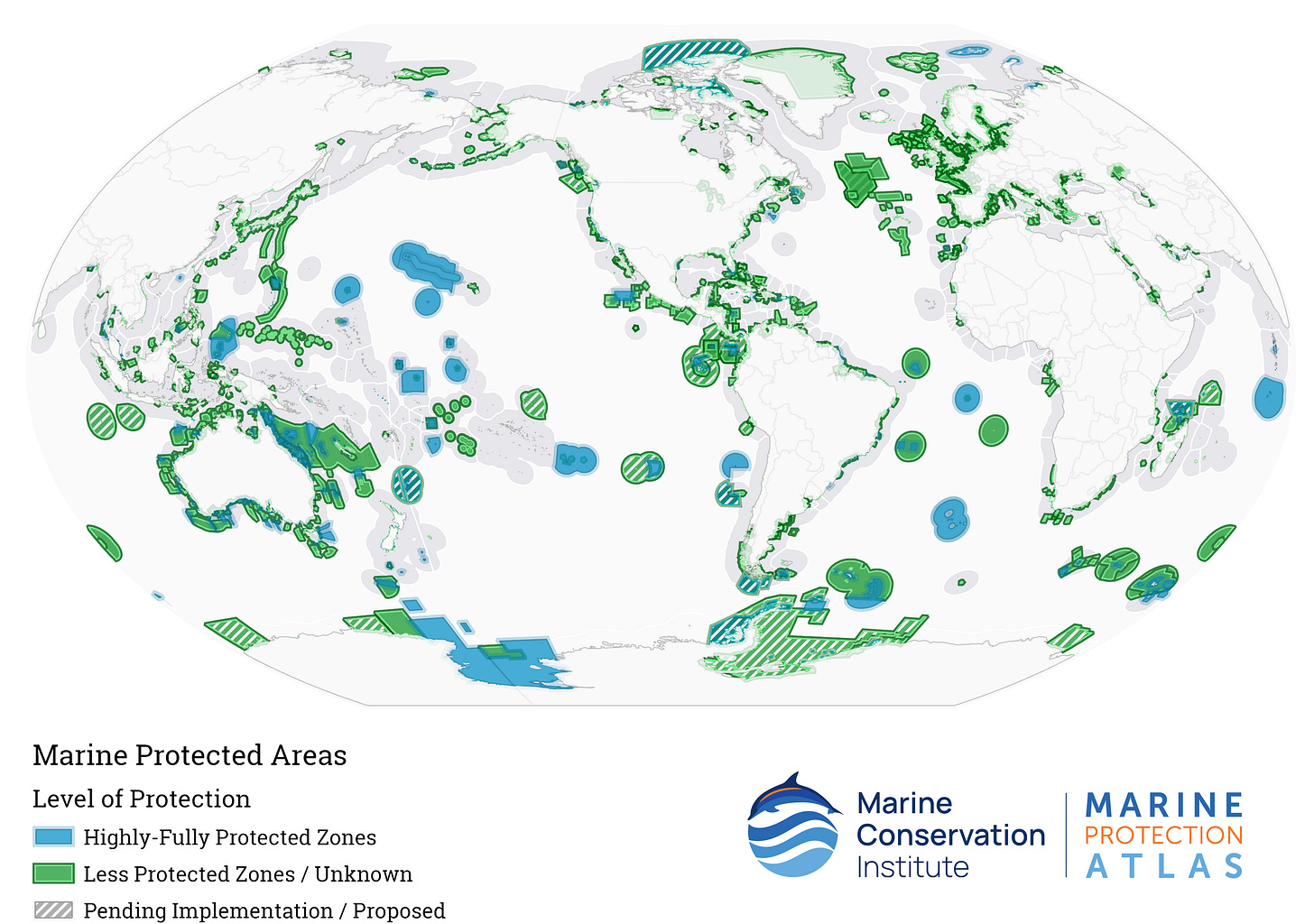

The High Seas Treaty takes its name from the area of the ocean it aims to regulate. Known as the “high seas” or interchangeably “international waters”, this region (dark blue above) lies beyond the authority of any existing nation-state and is only minimally regulated by current international law. This vast domain covers two-thirds of the ocean and nearly 50% of Earth’s total surface area. The remaining one-third of the ocean lies within Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) controlled directly by nation-states.

Extractive industries have historically taken advantage of the high seas’ Wild West nature. Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU) especially thrives in this expansive zone. The Patagonian toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides), for example, was nearly fished to extinction in the Southern Ocean in the 1990s and early 2000s. Sharks, roughy, tuna, squid, and krill are also targets.

International shipping lanes also traverse these unruly waters, endangering wildlife with pollution and ship-strikes. Future threats stalk too. Although there is currently no such thing as a wildcat deep sea mine, technological advancements will in theory make such illegal operations possible in the coming decades.

Zones of Fish Bliss

By far the most important provision of the High Seas Treaty is that which allows the creation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in international waters for the first time. MPAs are patches of ocean where governments have restricted human activity to preserve the natural marine environment. The levels of protection vary. In most cases fishing, shipping and tourism are at the very least limited, and may be banned altogether.

MPAs were controversial when they were first introduced - particularly their restrictions on fishing. But subsequent scientific studies have demonstrated they are the ultimate win-win. Protected areas turbocharge the recovery of marine ecosystems, and increase the fish catch in the surrounding waters.45

The most highly protected MPAs are currently the EEZs of uninhabited or scarcely inhabited islands controlled by Western nations - places like Wake Island in the Pacific, the Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean, or Ascension Island in the Atlantic Ocean. Scattered like blots of dripped paint across the map, these legacies of European colonialism have proved very useful to conservationists. But there are only so many of them.

Under the new High Seas Treaty, MPAs can now be created in the two-thirds of the ocean that do not adjoin terrestrial nations or island specks they control. The mechanism will be a Conference of the Parties (COP) process - similar to the annual climate change meetings - at which parties to the treaty can propose and approve new MPAs. The hope is to expand the percentage of the ocean under some level of protection to 30% by 2030, up from only 8% at present.

The largest remaining question is that of enforcement. The treaty provides for no hard enforcement mechanisms, relying on monitoring and reporting to national authorities. A more robust solution would perhaps be to allow a joint force of blue ocean navies (USA, China, France, or the UK) to police the MPAs on behalf of the United Nations. But that would require an amendment to the treaty and the abandonment of certain taboos surrounding national sovereignty.

For now, the expectation is that eagle-eyed surveillance and moral suasion will compel large fishing and shipping nations like China, Indonesia, Japan, and Peru to police their own fleets. And in so doing, allow at least some of our aquatic neighbors to live in peace.

The formal legal name of the treaty is ‘The Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction’. It is less commonly abbreviated as the ‘BBNJ Agreement’.