Meet The Endangered: Hawaiian Monk Seal

Like polar bears wandering across an Arizona desert, monk seals are animals that seem wildly out of place.

Nearly all seals live in the arctic and temperate regions of the world, their layers of blubber insulating them from the icy cold waters. But monk seals - uniquely - quit these shivering seas and decided to make a go of it in the tropics.

Monk seals first evolved in the North Atlantic, in the warm waters off the Mediterranean and North African coasts. And it was along the French stretch of those waters where they acquired their common name “phoques moines” (monk seals) - so given on account of their solitary nature and sleek, nearly-bald heads.

Hawaiian Monk Seals (Neomonachus schauinslandi) descend from a population that migrated to Hawaii between 3.5 and 11 million of years ago though the Central American Seaway, a natural passageway between North and South America that then connected the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

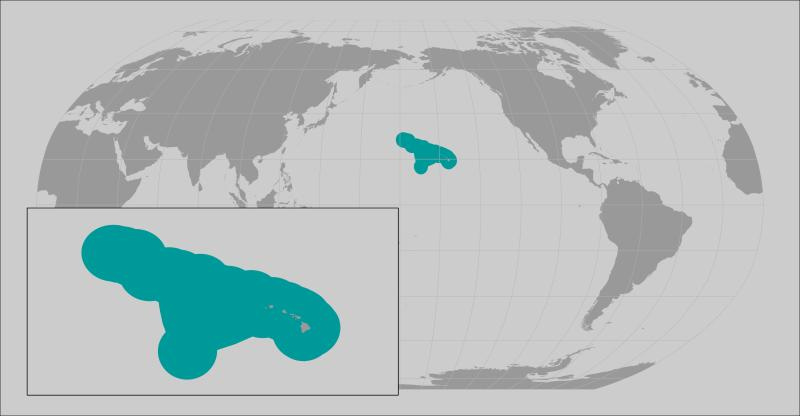

Monk seals once ranged from the central Pacific, through the Americas, upwards to North Africa and Europe. But the Caribbean population went extinct in the 20th century, and the number and range of Mediterranean monk seals have greatly reduced. All that remains of the global monk seal population today are thus two tiny endangered groups situated an almost comical distance apart - one in Hawaii (~1,400 individuals) and the other on the fringes of the Mediterranean Sea (~700).

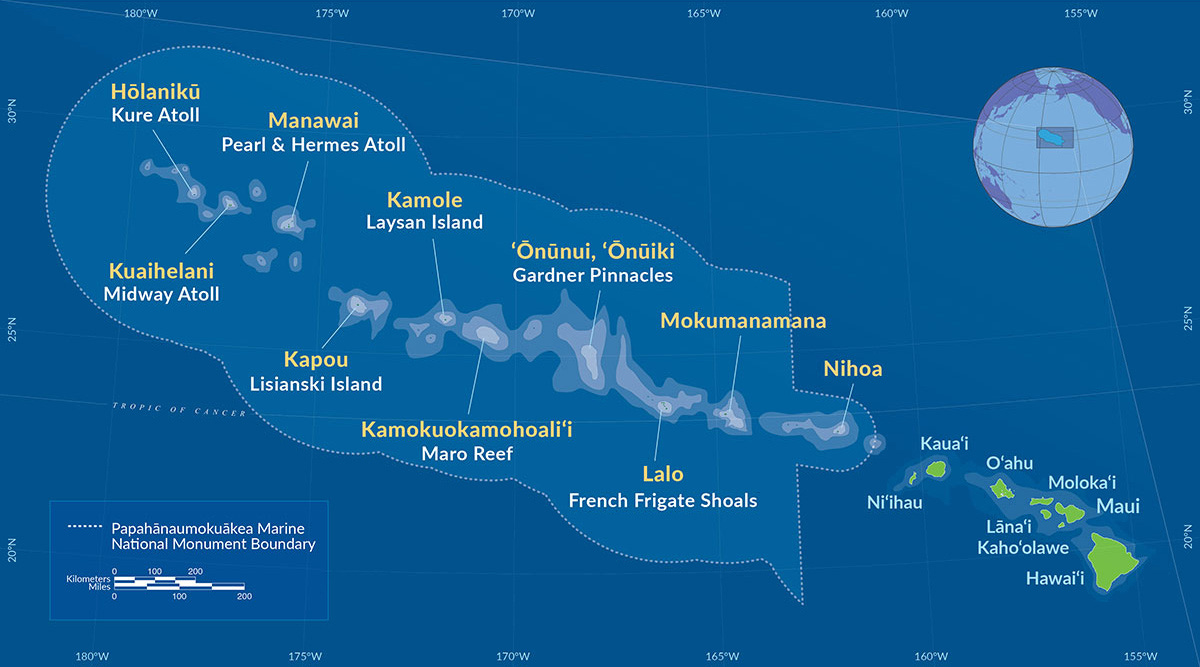

In Hawaii the seals are known in Hawaiian as “Ilio-holo-i-ka-uaua” which translates as “dog that runs in rough water” They are indeed extremely graceful and agile swimmers. Their sleek, torpedo-like bodies race though their native Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, the uninhabited string of reefs and atolls that jet outwards into the blue abyss separating the Hawaiian main islands from Asia.

Adult males range between 300 to 400 lb (140 to 180 kg) and are on average 7 feet (2.1 m) in length. Females are slightly larger, between 300 to 600 lbs (180 to 270 kg) and 8ft (2.4m) long.

Hawaiian monk seals are generalist eaters, feasting on a range of bony fish, crustaceans and cephalopods. Octopuses are a particular favorite. The seals can dive as deep as 1800 ft (550m) to forage the seafloor, but prefer shallower waters closer to shore.

Their adaptations to the heat are mostly behavioural. The seals instinctively seek out cooler spaces and often wait for nightfall to beach themselves on land.

Unlike their extremely gregarious cousins the sea lions, monk seals are extremely reclusive. They shy away from large groups and when on land prefer the isolation of small islets or atolls. This solitary behaviour - combined with a long gestation period of 10 months - makes it hard for the seals to maintain their demographic vigor.

The predations of humans haven’t exactly helped either. It was the seals’ thick layer of blubber that once made them a favoured target of our own species. Seal oil was a lucrative commodity used for soap manufacture, cooking oil and especially as fuel for oil lamps. The skins and meat were prized too.

An orgy of slaughter in the early 1800s very nearly ended Hawaiian Monk Seals altogether. Seal hunters from around the world descended on Hawaii as populations in other parts of the Pacific crashed from overhunting. Young monk seals were clubbed to death with hakapiks, a specialized tool resembling a pickaxe that crushed their skulls instantly. Adults were often shot with rifles from boats. Various reports exist of seals in that era being skinned while still alive, such was the avaricious haste of the hunters. Only a few plucky individuals managed to survive the culling.

Commercial American whalers and seal hunters are now themselves extinct, living on only as fictional characters in allegorical literature. Their industry perhaps best represents the backwardness of the pre-industrial economy in our collective imaginations. What kind of society requires burning seals and whales to keep the lights on?

Yet the physical scars of the 19th century whaling era persist. The wreck of the Two Brothers - a whaling ship from Nantucket, Massachusetts - was found off the French Frigate Shoals in 2008. She came to Hawaiian waters in 1823 to hunt seals, but ran aground and sank. The captain - one George Pollard - obstinately delayed abandoning ship and then made an abortive attempt to go down with her before being rescued in the end. It was the second such disaster under his command, which earned Pollard both an early end to his career and immortal fame as the inspiration for Captain Ahab in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick.

The most lasting relic of mankind’s pinnipedicidal rampage, however, lies not underneath the waves or betwixt the pages of philosophical fiction, but within the genetic code of the monk seals themselves. The 19th Century near extinction event caused genetic diversity to plummet, leaving them inbred and vulnerable to disease. The species averted annihilation, but its population is perpetually ill and won’t fully recover for centuries.

Also within the Hawaiian Monk Seals’ native range lies the wrecks of the Kaga, Sōryū, and Akagi, the famous Japanese aircraft carriers whose sinking at the Battle of Midway definitively turned the tide of the Second World War in the Pacific. In June of 1942, the entire world held their collective breaths and awaited the outcome of the fiercest and most decisive naval battle in human history. The seals had a front-row seat.

They may have been awed by the spectacle. But given their own experience with homo sapiens’ violence - they scarcely could have been surprised. It was only a matter of time before the maniacally aggressive apes floating on moving islands of steel turned their weapons on eachother.

The area around Midway Island is now at peace, protected both by distance and the postwar Pax Americana that still reigns in the Pacific. The entirety of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands - including the separately administered Midway - is now part of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM), a strict nature reserve that offers the highest degree of protection to the ecosystem and very limited access to the public.

The island chain has enjoyed some degree of protection since 1909, when Theodore Roosevelt created the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation. Over time the protected area has grown in fits and starts. George W. Bush watched a documentary on the region and subsequently decided to upgrade it to national monument status in 2006. In 2016 President Obama extended PMNM to its maximum possible size - abutting the very limit of the United States’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Within this area the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is responsible for nursing the species back to health, in cooperation with partner NGOs like the Marine Mammal Center. Hawaiian Monk Seals are a conservation reliant endangered species, meaning they only survive thanks to human intervention.

There is a deep irony in this arrangement. The very same maniacal apes directly responsible for the seals’ near extinction are now wholly responsible for their revival. The Marine Mammal Center estimates that 30% of living Hawaiian Monk Seals are alive as a direct result of its rehabilitation efforts.

Ke Kai Ola (The Caring Sea) is a hospital located in Kona, on the Big Island. It is the only veterinary hospital in the world dedicated solely to caring for these animals. Here, seals that have been injured by net entanglements or boat strikes are nursed back to health and then returned to the wild. Sick and malnourished seals end up here for treatment too. Genetically vulnerable to infectious disease, conservationists vaccinate the seals for extra protection.

In 2014 NOAA researchers discovered a malnourished female monk seal pup who weighed only 50lb (22kg), a scant one third of her healthy weight. They named her Pua ‘Ena O Ke Kai (Lit. ‘Misty Flower of the Sea’), took her to Ke Kai Ola, nursed her back to health in six months and then released her back into the waters surrounding Hōlanikū (Kure Atoll).

A team caught up with Pua ‘Ena O Ke Kai last year and discovered that she was a thriving 10-year old adult and a first-time mom, with a healthy-weight pup of her very own.

Thusly, we give up the spear.

Learn more about the Hawaiian Monk Seal and how get involved in its conservation at the Hawaiian Monk Seal Preservation Ohana and The Marine Mammal Center.