Britain Approves Modest Nuclear Expansion

Sensible Move to Shore Up Firm Low-Carbon Power

The United Kingdom’s government announced today an important new commitment to expand Britain’s nuclear energy program.

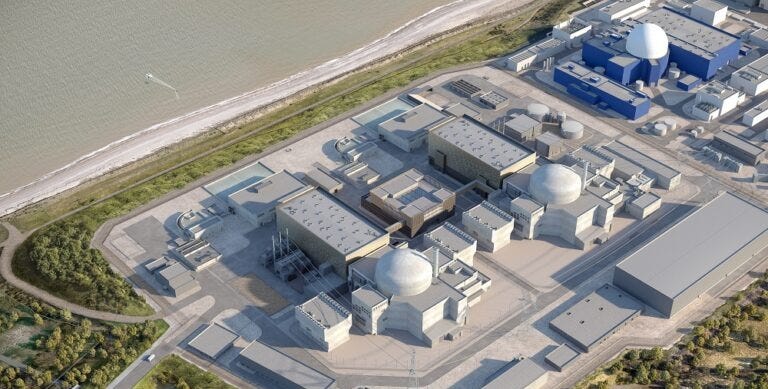

The expansion comes in two parts. The first invests £14.2 billion Sizewell C, a project that will build two new 1.63 GW EPR reactors at the existing Sizewell Nuclear Plant in Suffolk. The second awards a £2.5 billion contract to Rolls Royce to build three Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) of around .5GW each. Altogether the projects would add around 4.7GW of new nuclear capacity.

The move is an important one, as it assures Britain will have a reliable 24/7 source of low-carbon electricity on the grid for years to come even in the absence of cheap battery storage or imports from abroad. But the UK will not be the next France. In their obligatory write-ups many lazy journalists were to quick to open their drawer of poker metaphors, with Semaphor screaming to its audience “UK goes all-in on nuclear after years of debate”.

Such clickbait headlines are far from reality, however. If fully built-out, the projects announced today would equal about 13% of the UK’s 2024 electricity generation and bring nuclear’s total share around the 25% mark. That’s a decent amount of low-carbon generation that will help Britain meet its net-zero goals. But putting 13% of your chips on the table is hardly going “all-in”.

And even those figures are crude overestimates as they don’t take into account expected load growth between now and when the projects are finished or the expected retirements of older reactors that will shrink Britain’s nuclear fleet. In the end the UK isn’t massively expanding its nuclear program. The government is simply replacing old reactors with new ones to keep a small but important source of low-carbon generation on the grid for a few more decades.

Most of Britain’s future electricity generation capacity will be renewable. Wind is already the single largest generator, providing 29.96% of the UK’s electricity last year, compared to gas at 29.92% and nuclear at 14.51%. Wind is continuing to expand with an additional 13.3 GW of offshore wind alone expected to come online by 2030.

Solar is in its infancy on the cloudy British Isles, but did represent 5.6% of UK generation last year. Britain also balances the variability of wind and solar with Norwegian hydro imported via an undersea transmission cable. A similar cable to Morocco to import solar and wind is under development.